Always going against the grain, the surrealist painter Leonora Carrington experienced considerable isolation during her lifetime. Family strife and a male-dominated art world were two contributing factors. Despite the less than ideal circumstances, she never wavered from her intense desire to create.

__________________________

The imagination of children is a wonderful fact of life. It’s a kind of testimony to the rich and varied world around us along with the remarkable capacities of the human mind. A rainy afternoon stuck inside the house can spawn a brilliant and kaleidoscopic world of make-believe.

Unfortunately, such playful inventiveness tends to fade as we get older. The imaginative world takes on less and less importance in our day-to-day lives. Perhaps it’s because we feel as if the two worlds simply cannot co-exist in any feasible way.

For Leonora Carrington, the prolific but relatively unknown surrealist painter of the 20th century, these seemingly disparate worlds existed in a playful and mysterious symbiosis. She found it entirely natural to be actively involved in both —and that’s precisely what she did until she passed away in 2011, at the age of 94.

A documentary titled Leonora Carrington: The Lost Surrealist, allows viewers to step inside the world of this fascinating artist.

It’s a highly effective film, partly because of its creative style and delivery. When we see Carrington’s art, it’s often subtly animated, as if we are watching the active imagination of the artist take place in real time. The ethereal and beautifully haunting music adds a further element of liveliness.

Put all those ingredients together, and the end result is an hour long film that will compel many viewers to further explore this overlooked artist.

Born in Lancashire, England, in 1917, Leonora Carrington spent her youth on a large and impressive estate known as Crookhey Hall. Her wealthy father was part of the nouveau riche and was fully intent on climbing the next rung on the social ladder. Leonora’s mother, on the other hand, had a much lighter and gentler side, and would entertain her daughter with stories from Celtic and Irish mythology.

As for siblings, Leonora had three of them. None were sisters. Though there seems to have been no animosity between her and her brothers, Carrington’s childhood was characterized by considerable isolation.

The many solitary hours of her youth helped transport her into fanciful worlds that she might not otherwise have entered, or least not with so much vivacity and conviction. From a young age, she was immersed in drawing, writing, and creating. We see some of her childhood art in the film.

Given her highly creative personality, it is not terribly surprising that formal school was not a natural environment for her. Twice she was expelled from catholic boarding schools, though apparently not for anything egregious. “I think I was mainly expelled for not collaborating. I had a kind of allergy to collaboration.”

While she might not have been outwardly rebellious at school, she was pushing the boundaries—and her father’s patience—at home. The latter had clear expectations about the kind of woman she was to become: the wife of a wealthy and gentry husband.

Around the age of 18, she was sent to London in order to make her debut as a debutante. Dressed up and pushed into the environs of high society, the experiences were dreadfully miserable for Carrington. “I think her parents probably were at a bit of a loose end as to what to do with her next,” says an observer in the film.

Remarkably, her father allowed her to attend art school. For the first time in her life she found herself in an environment of like-minded people. She also found herself utterly enchanted by the style of surrealism, including the works of Max Ernst.

Fortuitously, Carrington happened to meet the man himself at a dinner party. The two of them took an immediate liking to each other, and quickly became lovers. Ernst was two and half decades older and a well-established artist. More significantly, he was also married.

It was the final straw for her father, whose patience with his intractable daughter was already thin. He cast her out of the family and the relationship was permanently ended. (Although the film isn’t explicit about her other relationships, it doesn’t appear that Carrington ever saw any of her family again—a terribly sad state of affairs, if true.)

Her time with Ernst brought her further into the world of art. When the couple lived in France, she was personally introduced to many famous artists, including Pablo Picasso and Salvador Dalí. She found herself with front one seats to one of Europe’s most explosive art movements.

Events far outside of her control, however, brought all of this to a painful end. In 1939, with World War II raging, the German-born Max Ernst was interned by the French army.

It was an event that absolutely devastated Carrington, who was still just in her early twenties. She was now without either family or soulmate. Emotionally and mentally shattered, she was forced into an asylum. (Carrington, who was also a talented writer, would later in her life describe the horrid experience.)

She somehow managed to escape the asylum and make her way to the Mexican embassy, where she spoke with Renato Leduc, with whom she was previously acquainted. A marriage of convenience allowed Carrington to stay out of the asylum, as well as leave the country. The couple moved to New York City, and shortly afterward, Mexico. Given the origin of the couples’ marriage, it perhaps isn’t surprising that it didn’t last long. They divorced in 1943.

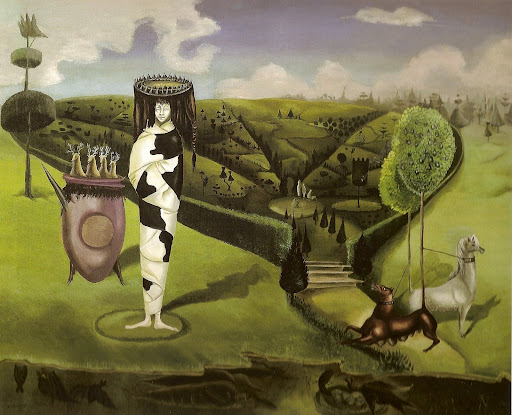

wikiart.org under Fair Use

Carrington stayed in Mexico, thousands of miles away from the place of her birth, and managed to build a life and come into her own as an artist. She created wonderfully inventive and dreamy works, like Green Tea. She also developed a strong social circle with other talented artists, many of whom were also expatriates. She was careful, however, to guard her status as an independently-minded female artist.

As one of her sons remarks, “She always had to remind people that she was an artist, and that she was a woman, and she had her own ideas about her art.” Carrington had no interest in reducing herself to the muse of a male artist (a state of mind that was true even in the midst of her passionate relationship with Max Ernst.)

Carrington was wise to be so cautious about this, given art history’s many stories of tumultuous liaisons. One thinks of an artist like Camille Claudel, who fell apart mentally and emotionally—and ultimately died in an asylum—after her relationship with Auguste Rodin fell apart.

Given the various setbacks in Carrington’s early life, it’s evident just how resilient, determined, and independent of a woman she was. Her son, Gabrielle, beautifully and poetically describes the outsider status of his mother’s entire life: “Art, that was her country.”

Thanks to this engaging and well-crafted documentary, hopefully many more people will become interested in one of that precious country’s most creative denizens.

You must be logged in to post a comment.