As far as I know, there are no squeaky toys inside the Jet Propulsion Laboratory located in Pasadena, California. I assume the same is true for burp cloths, pacifiers, and mobiles (even those with a solar system theme). But as we see time and again in the moving documentary Good Night Oppy, the scientists and engineers who created a pair of Mars rovers gave them a home full of love, care, and meticulous attention.

If you know little about prior missions to Mars, or have only a modicum of interest in space exploration, don’t write this documentary off. In fact, put it on your to-watch list.

There’s hardly a dull moment in its 90 minute run time, and you’ll come away feeling inspired by the teamwork and dedication on display. (It turns out that in order to send rovers to Mars, a cadre of diverse talent and incredible teamwork is needed.)

A particularly essential player was Steve Squyres, a planetary scientist and geologist. Inspired by the images of Mars that the Viking orbiters captured in the mid 1970s and ‘80s, he desperately wanted to find out if there was once water on the Red Planet. Humans making the trip to Mars was out of the question, but Squyres wondered if a rover could essentially act as a substitute. If so, then “we might find out the truth about Martian history.”

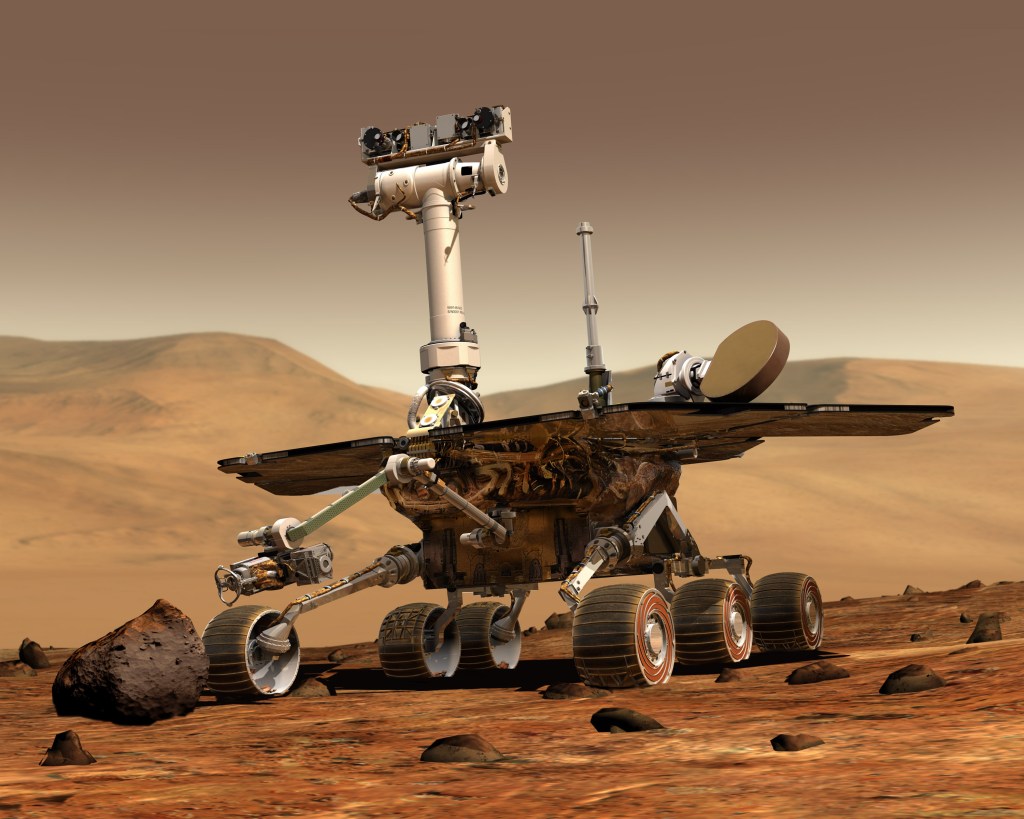

These yearnings of Squyres formed the germination of what would one day become Spirit and Opportunity, the two Mars Exploration Rovers launched into space on June 10, 2003, and July 7, 2003, respectively. But it took Squyres ten years of dutiful research and proposal writing until the project was finally greenlit by NASA.

Once the go ahead was given, Jennifer Trosper, an MIT-educated engineer who grew up on a farm in the midwest, managed the team. The goal was to “build two autonomous solar-powered rovers that could survive 90 sols [three months]” on Mars.”

Somewhat ironically, the mind-boggling complexity of sending rovers to a planet millions of miles away presented not only technical obstacles but a brutal fight against the clock. If the team failed to be ready by launch date, it would take 26 months for Mars and Earth to once again be properly aligned. (No pressure.)

In designing Oppy and Spirit, much emphasis was placed on making them resemble their makers—“It was a deliberate decision to make the characteristics human-like.” The rovers were even given 20/20 vision, though we’re never really told quite why. With the project costing a billion dollars, surely that choice wasn’t made merely because 20/20 is the normal, healthy sight for humans?

As the team worked on the immensely difficult task of desinging and building the rovers, they also had to figure out how to safely land Oppy and Spirit on Mars (each rover weighed nearly 400 pounds). Every day, every hour counted as the launch date approached.

The natural stress of the project was magnified by the memory of a failed endeavor that occured just a few years prior. In 1999, a $125 million project came to a spectacular end, all because units from English weren’t converted to metric (an embarrassing mistake even for a group of non-NASA engineers.)

When summer of 2003 rolled around, however, the dedicated team had come through. Oppy and Spirit—two rovers loved and adored by a group of engineering whizzes—left the arms of their parents, and Earth, and headed into the immense vastness of outer space.

Few of us have unleashed a cherished creation into the cosmos, but it’s not hard to share in the team members’ joys and sorrows as they recount what the project meant to them—and still does. Far from giving credence to the cliche of scientists and engineers being detached and unemotional, this team feels entirely natural in front of the camera. With exceptional energy, candor, and lucidity, they put us into their shoes during one of the most exciting times of their lives.

Adding to the poignant drama is narration from Angela Bassett, who’s mellifluous voice overlaps glitzy scenes of CGI that makes us feel like we’re actually on Mars with Oppy and Spirit, sharing in their adventure. To top it all off, Blake Needly provides a hauntingly cerebral score.

The best music we hear in the film, however, are the wake-up songs played for the twin rovers. Apparently it’s a tradition in human space exploration to wake up the crew in the morning with some music. Deny that tradition to Oppy and Spirit? No way! Among the songs chosen were “Roam” by The B-52’s and “Walking on Sunshine” by Katrina and the Waves.

Given the team’s obvious emotional attachment to the rovers, it’s little surprise that the documentary’s clear raison d’etre is showcasing the profoundly meaningful relationships that human beings can forge with their technological, space-exploring creations.

It’s not hard to see why the director went in this direction. Built to last roughly 3 months, the rovers defied all expectations: Spirit lived for 6 years, Oppy for 14 years. As the rovers sent back invaluable information about the geography of Mars, they also captured the hearts of their creators. For one team member, “Spirit was troublesome, Opportunity was Little Miss Perfect.”

When you spend years interacting with something (planetary rovers included), it’s nearly impossible not to develop some kind of personal attachment. And given how long the mission ended up lasting, many of the team members experienced life-changing events during its duration. One member was pregnant with twins; another saw the ravages of dementia afflict her grandmother.

These are things to keep in mind during the few places in the film where the melodrama feels a bit much. We tend to get antsy if we send a text and don’t get a response within a few minutes. Imagine the pit in one’s stomach knowing that after 14 years(!) of communicating with a rover stationed in outer space, you’ll never hear from it again.

It’s no wonder that when Oppy’s oncoming demise became clear to the team, special consideration was taken in selecting one final song. It was Billie Holiday’s “I’ll Be Seeing You.” Steven Squyres, the man who played such a critical role during every stage of the mission, picked it out. His face quivers with emotion as he tells us that “it’s a song about the ending of a relationship.”

Despite this riveting documentary leaving out a lot of details that would have been nice to learn—especially from the lips of these supremely passionate scientists and engineers—it’s such an uplifting experience that it’s hard to really care.

Good Night Oppy feels like a clarion call for us to unite in the pursuit of shared goals. At a time when everything feels so tragically divided, the deeply collaborative mission of transporting Spirit and Oppy to a planet far, far away feels especially moving.

You must be logged in to post a comment.